MAKING THEIR MARK

How a humble pair of yellow corduroys became the ultimate manifestation of irreverent preppy styleAt a certain point during the first decade of the 20th century—archival records seem to agree on sometime in 1904—students of Purdue University, in Indiana, began drawing on their pants. It wasn’t exactly the most countercultural act of rebellion (certainly it was received as more outré than antiestablishment), but within a few years, hand-painted pairs of golden corduroy trousers known as senior cords, or whistlers, for the distinctive whooshing sound a hardy set of corduroys can make while slicing through a crisp fall afternoon, solidified into a unique tradition in self-expression.

Before then, the students at Purdue were already subscribing to any number of sartorial self-sorting rubrics. Hats were an especially popular medium—wearing a bowler, a derby, a skull cap, or a sailor style called a pot would announce your class level or club membership, while the color of the button or crown of your wool ball cap could designate your major—a dense network of coding that dissected the entire campus into tribal affiliations and presumably had the effect of a years-long regional production of West Side Story.

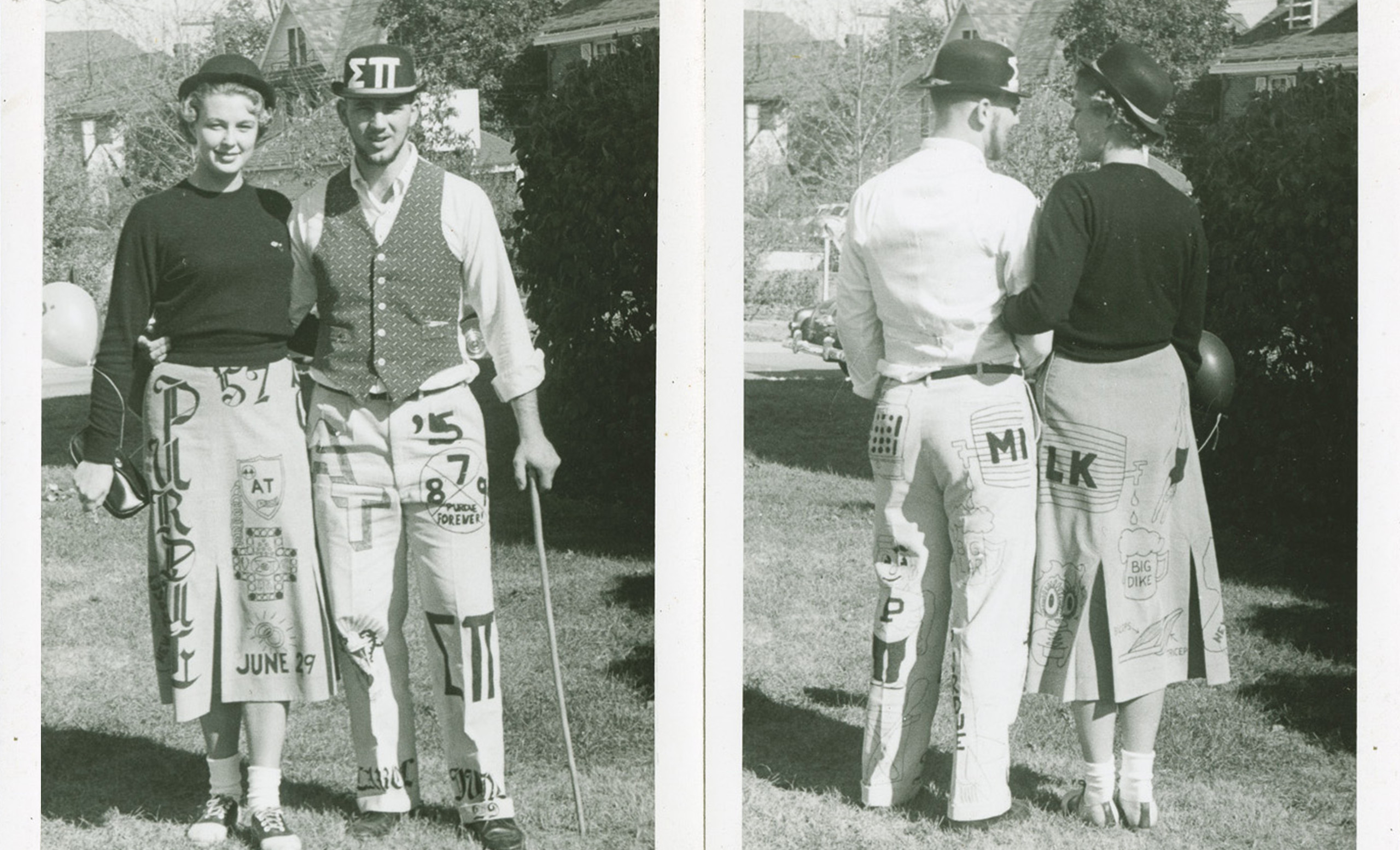

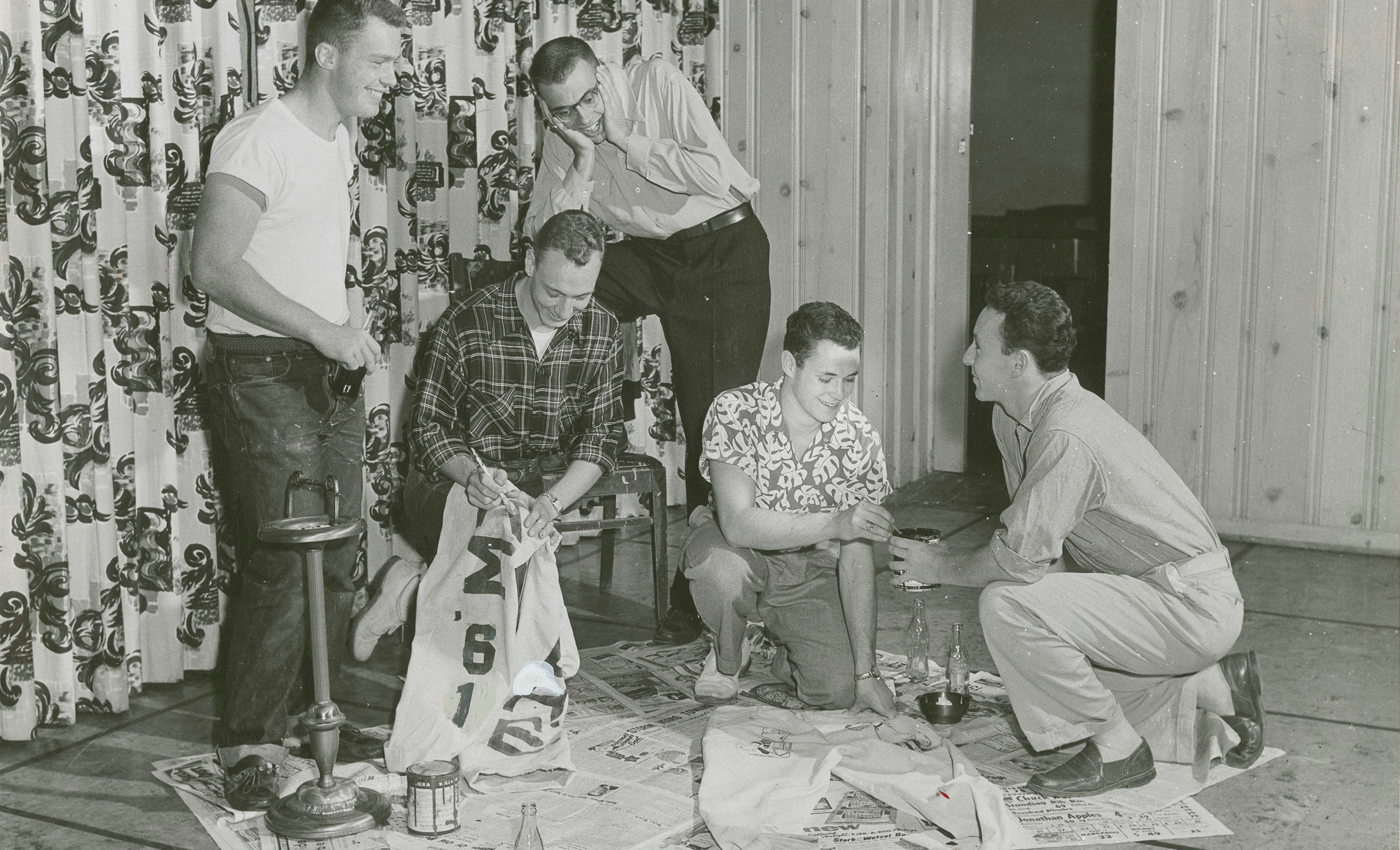

All of that would seem sufficient enough, but that was before a bolt of wheat-colored corduroy fabric in the window of Taylor Steffen Co., a tailor on Main Street in Lafayette, caught the attention of some Purdue seniors (the school colors were and remain gold and black), who purchased the fabric and requested it made into slacks, which they then scrawled on with paint or marker, as if graffitiing a bathroom wall. Students took the doodles, cartoons, and private jokes usually reserved for their yearbooks and transposed them wholesale to their pants, transforming them into literal, wearable badges of honor: colorful and brash cornucopias of confederation, friendships, and cultural minutiae, broadcast for the world (or at least the student body) to see. They decorated their cords with their fraternity or sorority insignia, nicknames, and symbols denoting their extracurriculars or dorm houses, their hometowns and states, even their disciplines (bubbling test tubes for chemistry, cartoon protractors for engineering).

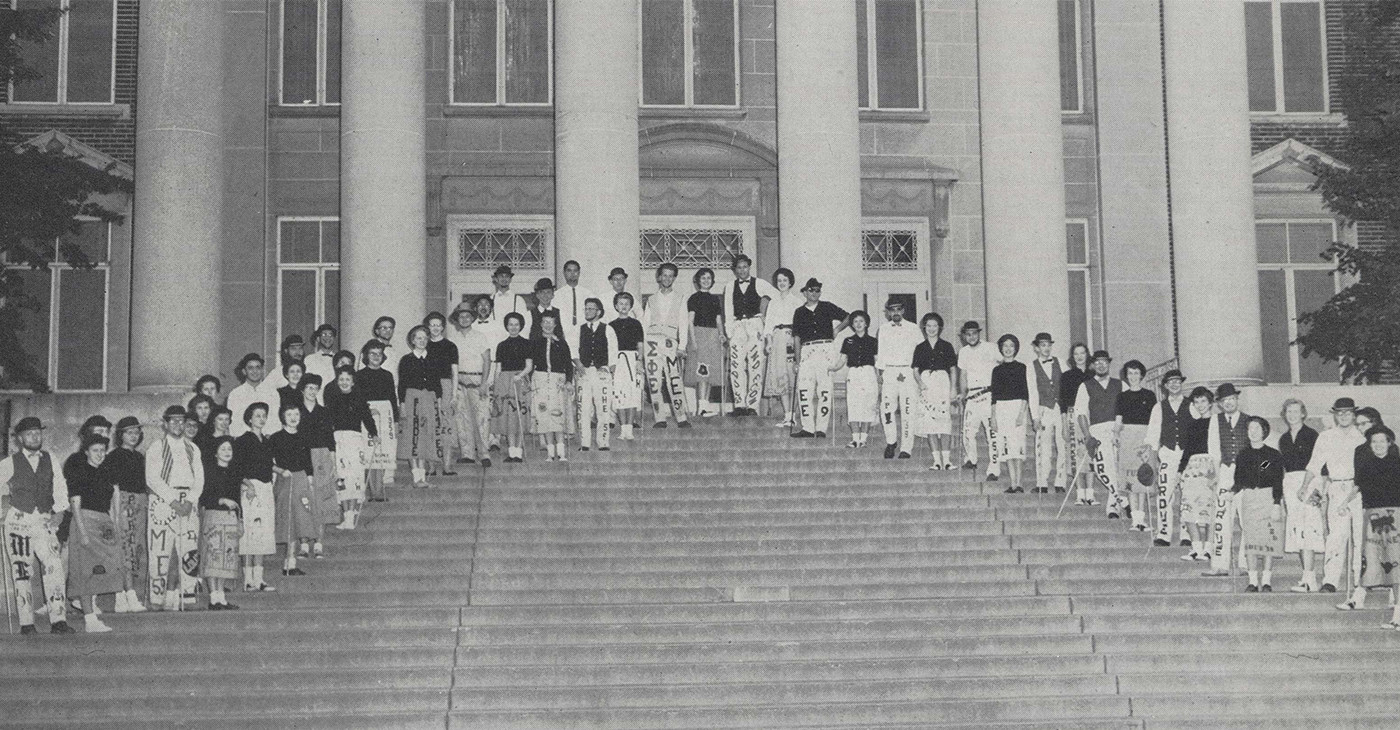

The style soon became de rigueur for the senior class, worked on in earnest during the lead-up to the opening game of the school’s football season and debuted en masse during a game-day parade. They were a kind of earned marker of arrival—by all accounts the Air Jordans of their day, or at least robust enough to allow the Taylor Steffen company to expand their advertising to the “Tailor Merchants for the Students.” As the tradition deepened, so did their execution, and by the late ’50s, the pants were synonymous with Purdue student life, and a particular phenomenon of collegiate Americana’s larger prep style of dress.

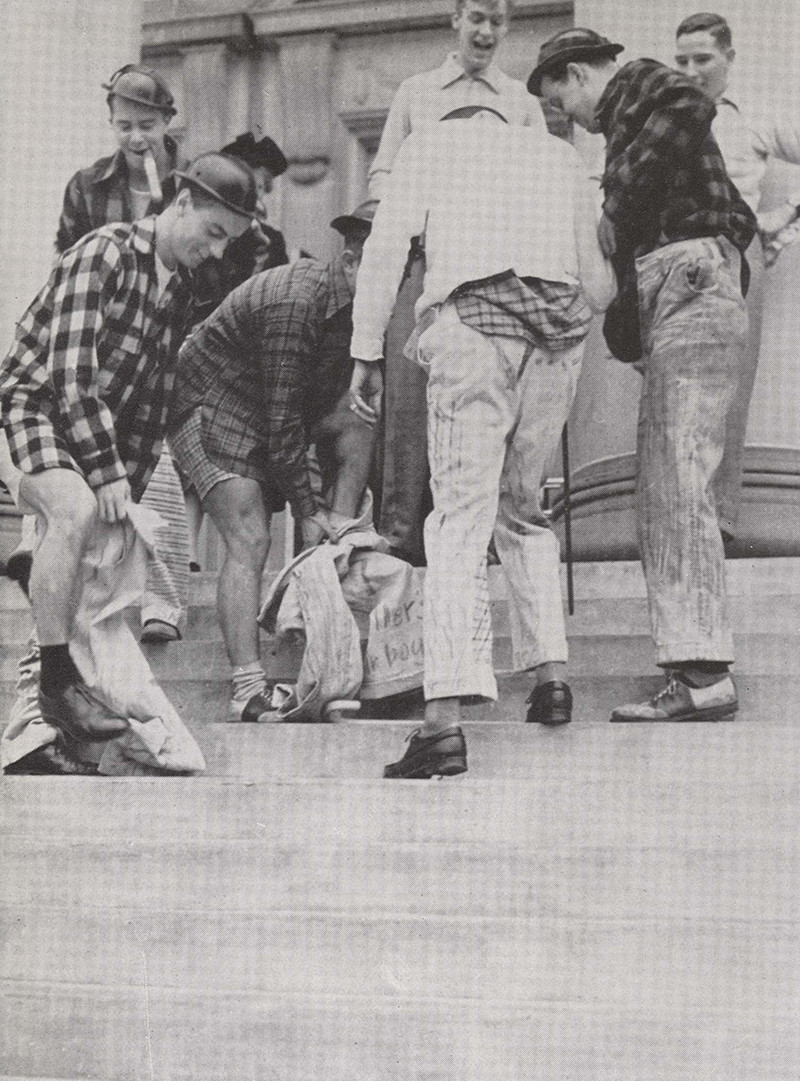

“It was part of the culture,” says Harvey Berliner, who graduated from Purdue in 1965. Practically all the seniors wore them and painted theirs with the history of their four years at school.” The cords, so freighted with meaning, spawned their own unique traditions, such as freshmen intent on capturing and defacing them. “You would try to find the seniors’ cords the night before they were supposed to be worn, which my pledge class did and painted them green,” Berliner recalls. “We paid dearly for that, but it was worth it.”

Elements of senior cords could become quite detailed, producing a winsome allover effect, a less dramatic precursor to tattoo sleeves: cartoon locomotives and boilermakers chugged up inseams, oblique glyphs pocked waistbands, and red inked roses (for the school football team’s first trip to the Rose Bowl, in 1967, in which Purdue dispatched the University of Southern California) ringed cuffs. Boys and girls would announce their exclusivity by painting halves of a single illustration across two pairs, which would join charmingly whenever they reunited.

When he became a senior, Berliner remembers staying up all night with his then-fiancée and now-wife, Edith, creating his cords. “She did most of the painting,” he stressed. In a snapshot taken the next morning, a youthful if a bit bleary-eyed Berliner proudly models his cords: a locomotive running across their seat and caricatures commemorating Berliner’s personal academic pilgrim’s progress adorning each leg—one picturing him as an eager freshman, the opposite as a beer-bellied upperclassman. “It was just a proud tradition, all the seniors walking to the football stadium together in their cords.”

Students at Purdue held on to the senior cord tradition until at least the ’70s, when the collegiate influence on American dress waned and sportswear ceased meaning genial separates and began meaning things specifically designed to wear for sports, like sneakers. But for a time they constituted a pre-internet social network, a tradition that trickled down to high schools in the region, and clothing by which one could become a walking billboard for one’s self, a potent mix of boosterism and autobiography and shared experience and all the self-identifying tastes that boil down to mutual understanding. There’s something to be said for fitting all of that on two legs.

- Courtesy of Purdue University