By Design

Ralph Lauren and Burleigh celebrate traditional craftsmanship with a one-of-a-kind collaborationSpend even a short amount of time in the Burleigh pottery factory in Stoke-on-Trent, England, and you’ll quickly get a lesson in living history. Everywhere you turn you find the last, the only, the unique. In an industry that has suffered greatly from mass production, falling demand, increasing costs, and downward-spiraling prices, Burleigh has stuck to its guns and stayed on in the heart of the area known as the Potteries, still making the highest-quality printed earthenware by hand, using time-honored processes with machinery from the 1940s and ’50s (plus some that dates back to 1889), all in the same factory that was purpose-built for the company in the late 19th century. Much of the staff have been there for decades, and in some cases their families worked there, too, passing their craftsmanship down through generations. “Burleigh uses craft skills developed over generations to create ware that spans fashion and trends,” says the company’s commercial director, Jim Norman. He goes on to explain, “Burleigh is genuinely different to all other ceramic brands, and it’s these differences that are increasingly being valued and recognized.”

A dedication to quality, tradition, and painstaking craftsmanship is what makes Burleigh and Ralph Lauren such a good fit, and the companies’ collaboration over the years has included some beautiful ranges, such as Arden, a late-19th-century design of twining hawthorn branches; Calico, an allover floral designed in the 1960s; and Regal Peacock, a favorite of Queen Mary’s.

Fittingly, this spring, the two storied names have come together on a series of three exclusive Ralph Lauren designs—the first time ever that Burleigh has featured anyone else’s original patterns on their pieces. “In Ralph Lauren we see people who are like-minded, understanding heritage in design and combining this with quality of production,” explains Burleigh’s company historian and retail manager, Jemma Baskeyfield. Harkening to the Americana graphics often found on Double RL bandannas, “Midnight Sky” features stars cast in a celestial color palette of indigo, black, and white across a range of wares, including mugs, plates, and bowls. “Garden Vine” and “Peony” are both anchored in florals, inspired by vintage batik textiles and single-color line work on early toile fabrics. Cast from fine earthenware strengthened with china clay, the collections include dinner and salad plates and bowls, rounded out by more whimsical serving pieces including a classic teapot and eye-catching Etruscan jug. Dishwasher- and microwave-safe, all three are meant to be mixed, matched, and loved for years to come. “The patterns clearly take inspiration from the great American style book, but are just like the best Burleigh designs, truly timeless,” says Baskeyfield, adding, “These are the heirlooms of the future, combining the heritage of the past, that beg to be used in the homes of the present.”

That sentiment—that each and every piece has a subtle depth and individuality that makes it truly unique—is what Burleigh has stood for since first opening its doors.

The story began in 1851 when Messrs. Hulme and Booth set up the Central Pottery in Burslem, one of the seven towns that together formed the most important, and prolific, centers of ceramic manufacturing in the world. The British took their tableware seriously (they still do) and had been making pottery on a large scale in the area for at least 400 years. Down the road could be found the factories of Wedgwood, Spode, and other great names, which had been established almost a century earlier; the skyline was dominated by the silhouettes of more than 2,000 bottle kilns (so called because of their shape; almost all now demolished), and the air was often black with the smoke of industry. In 1862, William Leigh and Frederick Rathbone Burgess took over the Central Pottery, renaming it Burgess & Leigh and introducing more intricate patterns to its expanding range of tableware. The firm flourished and, in 1889, moved to its current home, a purpose-built, steam-powered works called Middleport Pottery, perched on the eastern bank of the Trent and Mersey Canal. Today, the redbrick factory is a wonderfully picturesque maze, with labyrinthine passageways; steep, worn stairs; doors leading who knows where; attics stacked high with Victorian pottery molds (it’s the largest collection in Europe); and individual “shops” that are home to each of the different production processes.

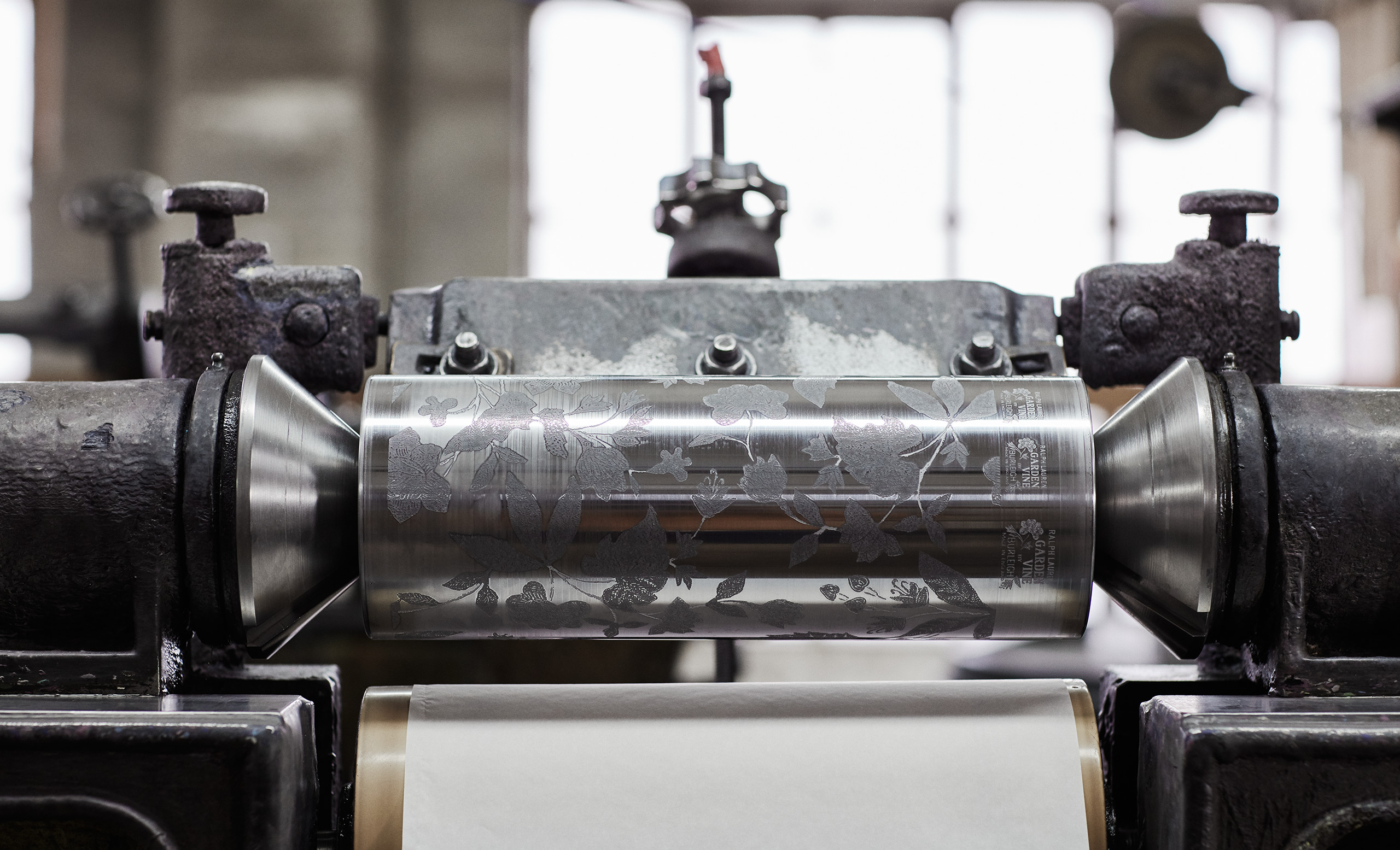

Since its earliest days, Burleigh has concentrated on a type of printing called underglaze transfer, a labor-intensive method developed more than 200 years ago. One by one, other companies have moved to cheaper and easier lithography, and now Burleigh’s the last one standing in this highly skilled game, which involves carefully cutting out the designs from printed tissue paper and rubbing them down (more vigorously than you might expect) onto each piece of pottery, making folds around curves and joining where necessary—especially tricky with, for example, a teapot covered in a dense pattern like Calico. List some of the other processes—jiggering (plate making), jollying (the forming of hollowware), fettling (trimming rough edges)—and these traditional terms give an even greater idea of just how much Burleigh’s past melds with its present. Making ceramics the Burleigh way is, as it always was, a complex business, and by the time each item reaches your table it will have passed through at least 25 pairs of hands, including the sponger and the caster, the biscuit brusher, and the glost placer.

In the early 20th century, Burgess and Leigh developed the brand name Burleigh, and during the 1920s the company’s decorative ware was highly sought-after. But a decline followed World War II, and although its future was secured with a sale to British ceramic manufacturer Denby in 2010, it still faced one huge problem: a decrepit factory that would be impossibly expensive to repair. Its savior? None other than Prince Charles, whose Prince’s Regeneration Trust bought the buildings and land and sensitively restored them in a £9 million, three-year-long project. There’s now also room for small businesses, a craft studio, a café, and a to-die-for factory shop with the most charming displays. The transformation has created a hub of enterprise and craftsmanship, and helped Burleigh more than double its workforce and rapidly increase its exports and online sales.

With this collaboration, Burleigh is heading firmly into the future. “The careful development of the Ralph Lauren designs has achieved something quite special—they fit the character of our ware,” says Norman. “Achieving this was very important to us and we’re really proud of the results.”

- © RALPH LAUREN CORPORATION

- © BURLEIGH POTTERY