Master Of

Road And Sky

Unpacking the life of inventor, aviator, and artist Robert Edison Fulton Jr.

Robert Edison Fulton Jr. liked inventing things, from top-secret military devices to pithy turns of phrase. “One measure of a man is what he does when he has nothing to do” was a favorite motto of his. In his home studio, he kept a sign that read “Home is not a house. Home is a road.”

Born in 1909, Fulton had travel in his blood. His ancestors—the Robert Fulton who invented the steamboat may or may not have been one—ran stagecoach lines in the West and created the Greyhound bus company. His father was president of Mack Trucks and had young Robert working on engine blueprints at an age when most boys are learning to throw a baseball.

Fulton made the most of his privileged pedigree. He was a young passenger aboard a flight from Miami to Havana in 1921—the earliest days of commercial air travel. Two years later, he witnessed the opening of King Tut’s tomb in Egypt.

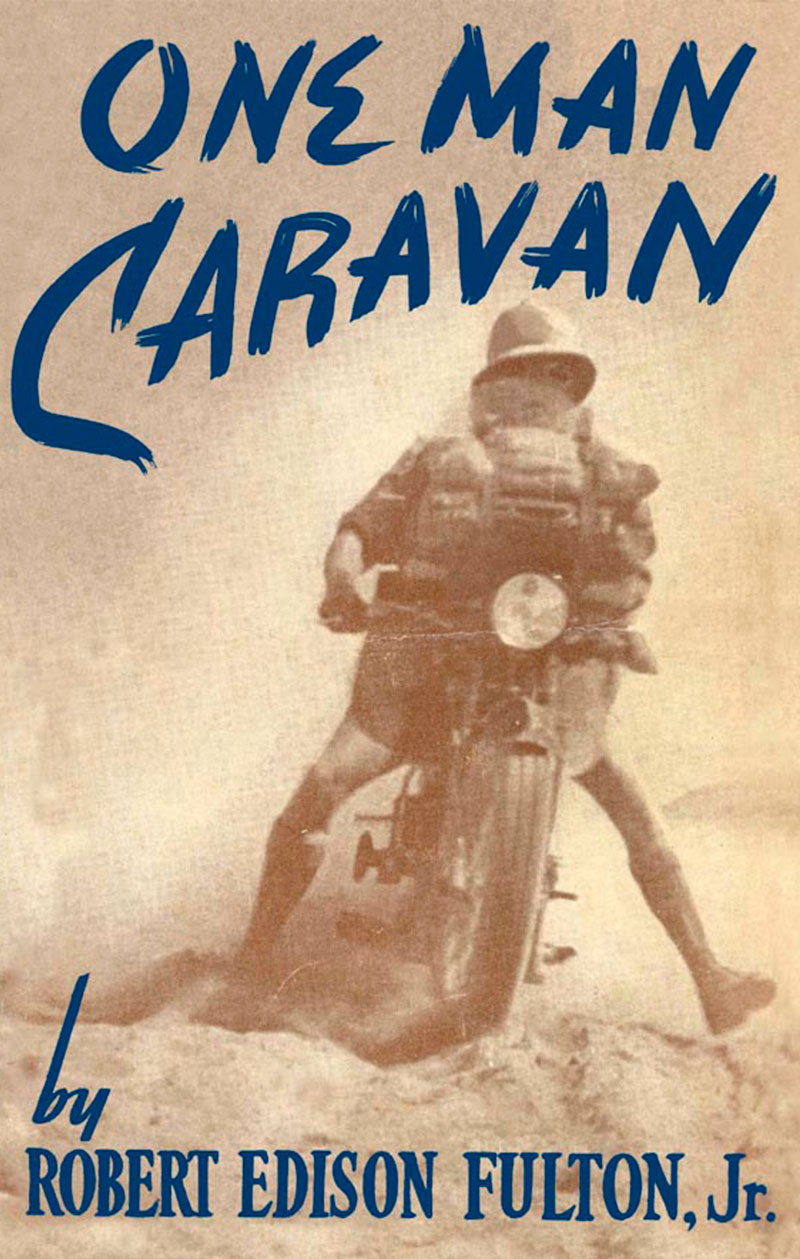

But the so-called curse of the pharaohs didn’t touch the blue-eyed traveler. Fulton seemed to coast along the road of life, buoyed by resourcefulness and his affable, freewheeling nature. The first lark that earned him notice was the 25,000-mile motorcycle journey that he undertook soon after finishing college. Remarkably, he sort of bumbled into the whole thing.It was 1932. He had just received a degree in architecture from Harvard and was completing an additional year of study in Vienna. One evening in London, at a dinner party, a female companion asked Fulton what he planned to do next. “Ride a motorcycle around the world,” he improvised, presumably to impress his interlocutor. But another guest overheard—one who happened to own a motorcycle company. The stranger offered to provide the vehicle, and Fulton’s bluff was called.

It says much about the man that Fulton went ahead with it. He taught himself to ride in London and soon found himself headed toward Japan on a customized Douglas two-cylinder. Though he started out in style, he jettisoned his evening clothes in Greece. The rest of the way, Fulton’s luggage consisted of little more than his cameras and his toothbrush.

The original character-building plan had been to study historic architecture. But Fulton found that he was much more drawn to the people he encountered. The solo traveler would arrive in Turkish or Afghan villages seemingly out of nowhere, caked in mud, astride his two-wheeled stallion. The people were equally drawn to him—usually for better, sometimes for worse. But based on the jovial accounts in One Man Caravan, Fulton’s memoir of the trip, it took more than language barriers and the occasional night in jail to faze him.

He was buoyed, he wrote, by “that inspiring factor in travel—the welcoming hand of the interested stranger.” And though he kept a hidden pistol on him, the only use he had for it was as a hammer to repair his motorcycle.

Having traversed Europe and Asia, then taken a boat to San Francisco and ridden across America, Fulton returned to New York. The films and photographs of his trip—which may well have been a world’s first—helped land Fulton a job taking pictures for Pan American airlines.

Thus his obsession with aviation began in earnest. Fulton directed his creative powers skyward as World War II loomed, inventing an early flight simulator that made use of panoramic horizon photos he’d snapped atop the Empire State Building. He also created a gunnery simulator, which he sold to the Navy for a handsome profit.

“Inventions have a way of spawning other inventions,” Fulton once noted. He’d taught himself how to be a pilot at this point and preferred flying himself to his military appointments. But there was a problem: finding ground transport from the landing strip, especially with taxi drivers constrained by wartime fuel rationing.

Enter Fulton’s Airphibian, which caused a press sensation when he unveiled it in 1947. Five minutes of easy disassembly transformed it from a plane into a funny-looking car. Charles Lindbergh praised the contraption. But the costly certifications process eventually forced Fulton to sell the company, putting him at the mercy of new backers, and the Airphibian never went to market.

More military inventions followed, the biggest of them designed for airlifting personnel out of hostile territory. Fulton’s Skyhook system was applied in several covert operations and, more famously, to scoop up Sean Connery’s 007 in the stylish coda to Thunderball. Fulton claimed the US government had a plan to Skyhook the Dalai Lama out of China. (In the end, His Holiness made his escape on foot.)

In later life, comfortably holed up in Connecticut, Fulton put more of his creative energy into artwork. He went back to aerial photography, flying upside down in his P-51 Mustang to get better shots. (Let us pause to note that we are talking about a man in his 60s here.) He made sculptures, too. Many of them he kept at his 40-acre estate in Newtown, where he worked out of a refurbished barn stocked with personal memorabilia, from travel souvenirs to the polar bear–skin rug he had played on as a child.

A friend described the aging Renaissance man as “genteel, kind, and serious—and ready and able to philosophize about any important topic in the world today.” When he wasn’t out tinkering, of course. When Fulton died—in 2004, at age 95—he left behind his old Douglas motorcycle, which he’d rebuilt to look like new.

Though he often dreamed of being airborne, he claimed it was the motorcycle journey that had changed him most. He had said something outlandish. Where had the idea come from? No matter. And then he’d simply gone ahead and done it.- Photograph courtesy of Whitehorse Press

- Photograph courtesy of Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum