When Georgia O’Keeffe was 45, she had a nervous breakdown. The artist synonymous with oversize colorful flowers hadn’t painted in nearly a year and had missed a deadline for her most significant commission to date, a mural at Radio City Music Hall. Making matters worse, her husband, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, was having an affair.

At an all-time low, she needed more than a getaway. She needed to get off the map. So in 1933, O’Keeffe sailed to Bermuda. Only 774 miles off the shore of New York City in the mid-Atlantic (not the commonly-confused-for Caribbean), she checked into a remote bungalow.

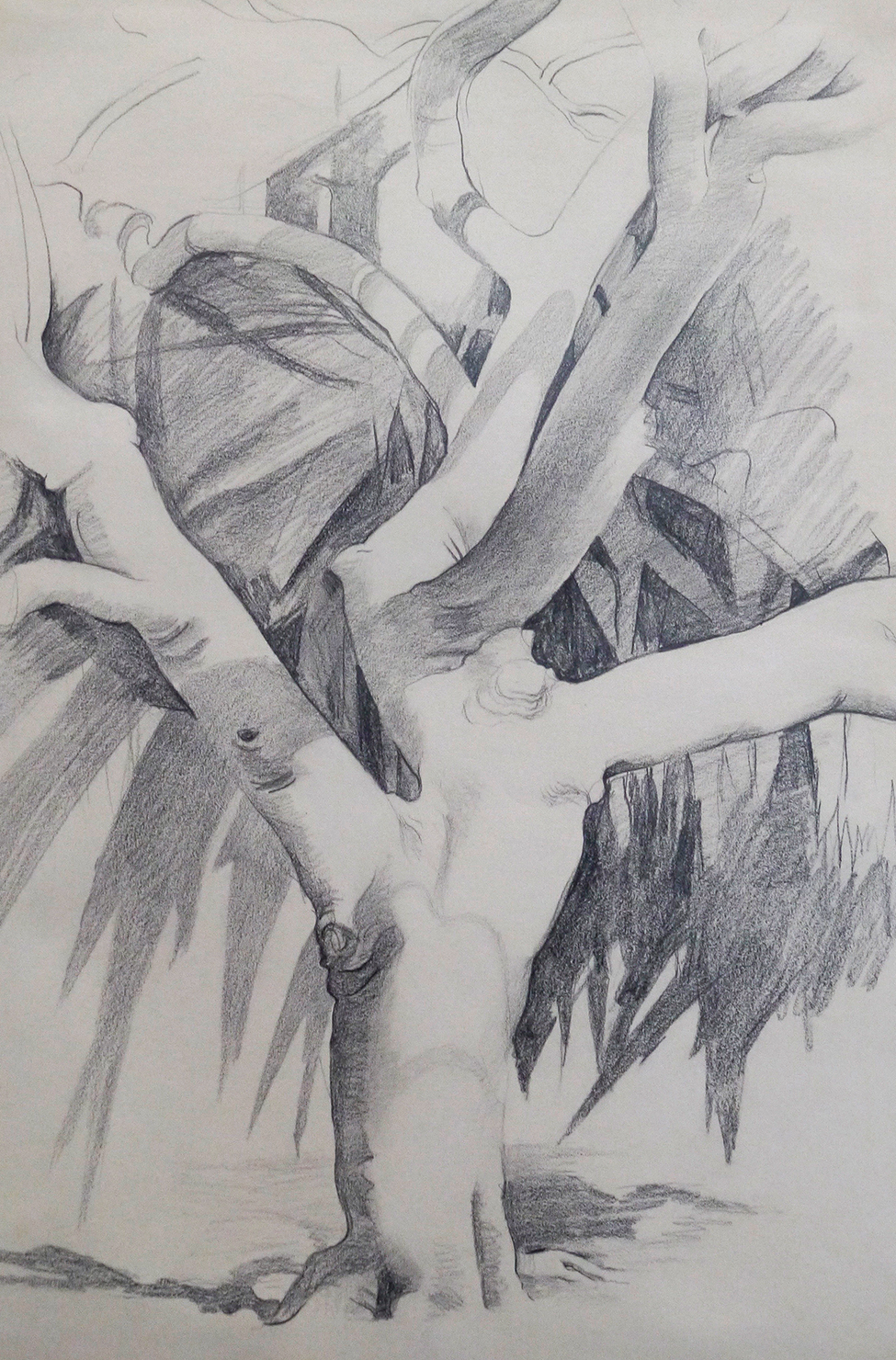

Just outside her door bloomed the same pink and yellow hibiscus she would later paint in Hawaii and receive unprecedented praise for. But O’Keeffe wasn’t in the mood yet for color. During her two years of solace in Bermuda, she fixated on the complex root systems of the island’s banyan trees, making sense of their tangled shapes with graphite drawings. Today, two of these small-scale sketches hang at the Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art, which appropriately overlooks the Bermuda Botanical Gardens.

Bermuda’s untouched beauty, free of commercialized tourist attractions, was then and is now a rarity in the curated world of luxury travel. The island—mysterious and seductive in its remoteness—has long recharged the senses and fueled creativity.

“You go to heaven if you want to, I’d rather stay right here in Bermuda,” Mark Twain said in 1867 on a return voyage from a five-month excursion to the Black Sea. Twain’s last stop before New York was the island first discovered by the Spanish in 1505 and settled by the British a century later. “Bermuda was a paradise, but one had to go through hell to get there,” he wrote of the isolated 21-square-mile island that nonetheless beckoned him back for extended escapes throughout the rest of his life.

Fast-forward to today and you’ll find that in-the-know travel sets still prefer Bermuda over massive resort-ridden islands. And as with Twain and O’Keeffe before them, the remote splendor and low-key appeal is exactly what keeps them coming back.

A hallmark of that sentiment is the Coral Beach and Tennis Club—a members-only local that embraces its “lost in time” existence. Since its founding in 1948, not much has changed at the classic spot. Tennis whites are required on the clay courts, rum swizzles are sipped under sun-bleached yellow striped beach umbrellas, croquet is played on the front lawn, and men are required to don formal Bermuda dress (blazer, Bermuda shorts, and wool knee socks) to dinner. The weathered wrought iron outdoor furniture, faded floral chintz sofas, and chipped pink façade are all part of the worn-in, preppy charm.

While the island is home to American dynasties like the Johnsons, Bloombergs, and Perots, and a hub for reinsurance and offshore finance, you won’t spot chains like Starbucks, CVS, or Uber in Bermuda. Even Amazon delivery is intentionally complicated to encourage shopping local. The lack of convenience frustrates some, but it’s all a calculated effort to preserve nature’s beauty.

“Bermuda didn’t miss going global; it’s all by design,” says Colin Campbell, a Bermudian architect at the local firm OBMI. Campbell points out that in the early 1900s, laws were passed prohibiting neon signs and any outdoor signage in general with letters larger than 15 inches. “As a consequence, there is a discreetness here.”

What became law started out of necessity with resourceful early settlers turning to the natural materials of the island to build the streets and homes that still stand today. “We are out in the middle of nowhere, so we have had to evolve and create our culture,” says local historian Kristin White, who helms a bookshop in a circa-1750s building on Water Street in St. George’s.

From the foundations and walls carved from local limestone called coral (strong enough to withstand centuries of hurricanes) to the white stepped roofs designed to catch and retain fresh rainwater, the elements of a traditional Bermudian home are built to last.

And with conservation top of mind, Bermuda’s National Trust is committed to preserving the weathered, pastel-colored cottages that have become synonymous with the aesthetic sensibility of the island. In fact, they still stand strong in such large numbers that two decades ago the entire town of St. George’s was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site. “The history isn’t behind glass or a rope; you are walking past and into centuries-old properties that tell stories,” White says.

In his book Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion, Twain summed up the island’s seductive charm: “Bermuda is the right country for a jaded man to ‘loaf’ in,” he wrote. “There are no newspapers, no telegrams, no mobiles, no trolleys, no trams, no tramps, no railways, no theatres, no noise, no lectures, no riots, no murders, no fires, no burglaries, no politics…” As with so many of Twain’s famously keen observations, the sentiment endures.

- Courtesy of Getty images

- © Ralph Lauren Corporation